Robert Rauschenberg working on Oracle (1962-65) in his Broadway studio, New York, 1960s. Photo: Unattributed

Crank Up The Volume -- 100 Years of Rauschenberg's Sonic Legacy

For Rauschenberg, art was never just for the eyes. The artist, who shattered the boundaries of painting and sculpture, invited viewers to tune in, touch, and, crucially, listen. “Listening happens in time. Looking also had to happen in time,” Rauschenberg declared in 1963. A tireless experimenter, he created artworks that provoked a dialogue with the viewer—sometimes, literally.

Collaborating with pioneers like composer John Cage and engineer Billy Klüver, he transformed galleries into interactive soundscapes, so much so that a 2017 New York Times review of Robert Rauschenberg: Among Friends, a retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), called the exhibition “definitely noisier than your average museum show.”

Now, as the world marks the Centennial of his birth, Rauschenberg’s groundbreaking sonic works are resonating anew—reminding us to pause, pay attention, and ask ourselves: in the “gap” between art and life, what do we hear?

Some of Rauschenberg’s earliest sound experimentations can be seen in Elemental Sculptures (1953/ca. 1955), a series of constructions made from materials found in the neighborhood surrounding his Fulton Street studio in New York. The playful Music Box (ca. 1955) was designed for hands-on interaction—shake the wooden box, and loose stones rattle against the nails lined inside, producing a spontaneous sound composition, much in the style of Rauschenberg’s friend, the experimental composer John Cage.

Debuting alongside paintings by Cy Twombly at the Stable Gallery in 1953, Rauschenberg’s works invited viewers to move, rearrange, and even play them, blurring the line between art and audience. Marcel Duchamp himself could not resist picking up Music Box at the show, quipping, “I think I’ve heard that song.” Duchamp’s visit left Rauschenberg “speechless,” he told Barbara Rose in a 1987 interview.

Today, Music Box is featured in Five Friends: John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Cy Twombly at the Museum Brandhorst in Munich through August 17, 2025.

Rauschenberg continued to explore sound in his groundbreaking Combines (1954–64). These artworks blurred the distinctions between painting and sculpture and often incorporated found objects. For his 1959 Broadcast, hidden behind the canvas, three live radios hum and chatter, their dials poking through the surface for viewers to twist, adjust the volume, and change the stations.

In 1962, a visit to Andy Warhol’s studio marked a turning point for Rauschenberg. Inspired by Warhol’s silkscreen technique, he began incorporating the method into his own artworks, layering photographic imagery with paint and found materials. Among these, Dry Cell (1963) stands out for its screenprinted image of an army helicopter, a motif that also appears in many Silkscreen Paintings (1962–64), and for its inventive mechanics.

Made in collaboration with engineer Harold Hodges in 1963 , Dry Cell is a battery-powered assemblage. In January of the following year, Rauschenberg included the artwork in the exhibition For Eyes and Ears at Cordier & Ekstrom gallery in New York. Though many of the artworks in this group show made sound, Rauschenberg instead created a work that reacted to sound: speak to the artwork and the sound is picked up by a microphone, causing part of the sculpture to spin.

Dry Cell is now featured in Sensing the Future: Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.), organized by the Getty Research Institute, on view at LUMA Arles through January 11, 2026.

Rauschenberg’s partnership with Bell Labs scientist Billy Klüver, sparked during Jean Tinguely’s kinetic Homage to New York in 1960, led the artist to realize some of his most ambitious sound artworks: Oracle (1962–65) and Soundings (1968).

Built with a ventilation duct, an automobile door, and more, Oracle is a five-part sculptural environment. Using a remote control, viewers can change the channel and control the volume of radios within the elements, creating a shifting mix of voices, static, and music—a sound experience similar to hearing radios playing from open windows as one walks down a busy street. As he put it in a 1991 draft for a statement published in Art in America, the goal was “to make a musical instrument that could be performed on with or without sophistication.”

This spirit of collaboration and innovation did not stop with Oracle—it laid the groundwork for Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.). Rauschenberg and Klüver co-founded this pioneering initiative in 1966 with artist Robert Whitman and engineer Fred Waldhauer to make technology more accessible to artists. In the same year, they produced 9 Evenings: Theatre & Engineering, an event that brought together visual artists, dancers, choreographers, scientists, and engineers.

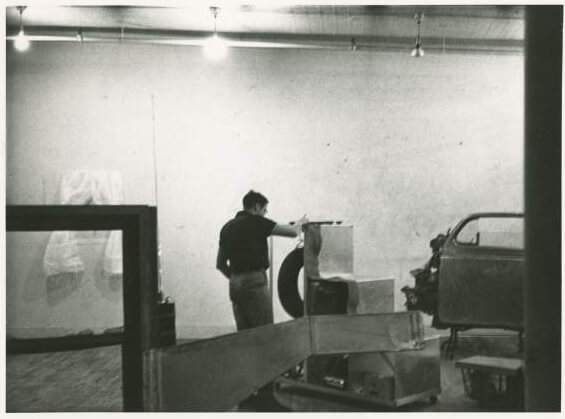

In 1968, Rauschenberg collaborated with Klüver again, as well as with Hodges, who had helped him realize Dry Cell in 1963. Together, they made Soundings, a monumental, interactive installation. Spanning thirty-six feet, Soundings is composed of three layers of Plexiglas: the front is mirrored, while the inner layers are screenprinted with images of Rauschenberg’s kitchen chair from every angle. Concealed electric lights, triggered by microphones, respond to the sounds made by visitors—clapping, speaking, or singing—illuminating and exposing the imagery. A 1968 reviewer described visitors’ enthusiastic reactions to Soundings and being imaginative with sound themselves: “they sing, whistle, yodel, shout and cough.”

Soundings is currently on view at the Museum Ludwig in Cologne.

Throughout 1968, Rauschenberg continued to explore how to make sound visible. Inspired by nature, the bubbling “paint pots” of Yellowstone National Park, Mud Muse (1968–71) is a room-sized aluminum-and-glass vat filled with nearly 8,000 pounds of bentonite mud. Hidden inside, a complex network of air valves and a sound-activated system bring the mud to life: recorded sounds triggered bursts of compressed air, making the surface bubble and churn in a constantly changing, unpredictable display.

When Mud Muse debuted at LACMA’s landmark 1971 Art and Technology exhibition, visitors were so intrigued that some even unexpectedly scooped up mud to smear on the museum walls. Organized by Maurice Tuchman, the show featured collaborations between engineers and artists such as Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg, Richard Serra, Warhol, Whitman, and many others.

More than fifty years later, Mud Muse is a highlight of the exhibition The Subterranean Sky: Surrealism in the Moderna Museet Collection, on view in Stockholm through January 11, 2026. The Museum was a recipient of a Centennial grant from the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation.

After moving to Captiva, Florida in 1970, Rauschenberg began using new materials and techniques. In the mid-1980s he combed the island’s scrapyards for discarded metal—gas station signs, auto parts, and other industrial remnants—which he reimagined as part of his Gluts series (1986–89/1991–94), a series of wall-mounted and freestanding sculptures. Both animated and playful, Intersection Glut (1987) invites direct interaction: press its silver button and a car horn rings through the gallery. Paired with a traffic sign, and as suggested by the title, the sound instantly evokes the hustle and noise of a busy intersection.

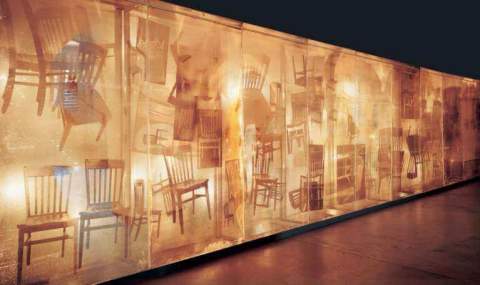

From 1997 through 1999, the major exhibition Robert Rauschenberg: A Retrospective traveled to several locations of the Guggenheim Museum in New York; the Menil Collection, the Contemporary Arts Museum, and the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston; and to Museum Ludwig in Cologne, before going to the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao. For the final venue, Rauschenberg created a site-specific sound sculpture, Earth Pull (1998), inspired by Frank Gehry’s iconic architecture of the museum. Suspended from the third-floor balcony, Earth Pull featured ropes, lights, and concealed amplifiers, with stretched colored cords cascading three stories down to the main lobby below. Visitors pulled on the ropes alighting bulbs and prompting the sounds of horns, turning spectators into participants, and filling Gehry’s atrium with new energy.

Rauschenberg’s fascination with sound ran throughout his career, from interactive sculptures to collaborations with composers, engineers, and dance companies. In 1983, he even won a Grammy for his cover design for the Talking Heads album (Speaking in Tongues). For contemporary composer David Lang, interviewed by the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 2017, Rauschenberg saw that “there shouldn’t be a distance between composer and performer, just as he saw there there shouldn’t be a distance between artist and choreographer, or artist and costumer, or composer and poet.” These experimentations across disciplines, says Lang, are no small feat: with all senses now awake, they make us “feel like [we] can live a bigger life.”