Art in Context

Here, individual artworks by Rauschenberg are examined within the scope of the artist’s work and life and within a broader art-historical and historical context. Works are also considered in relation to archival material often residing within the foundation’s holdings.

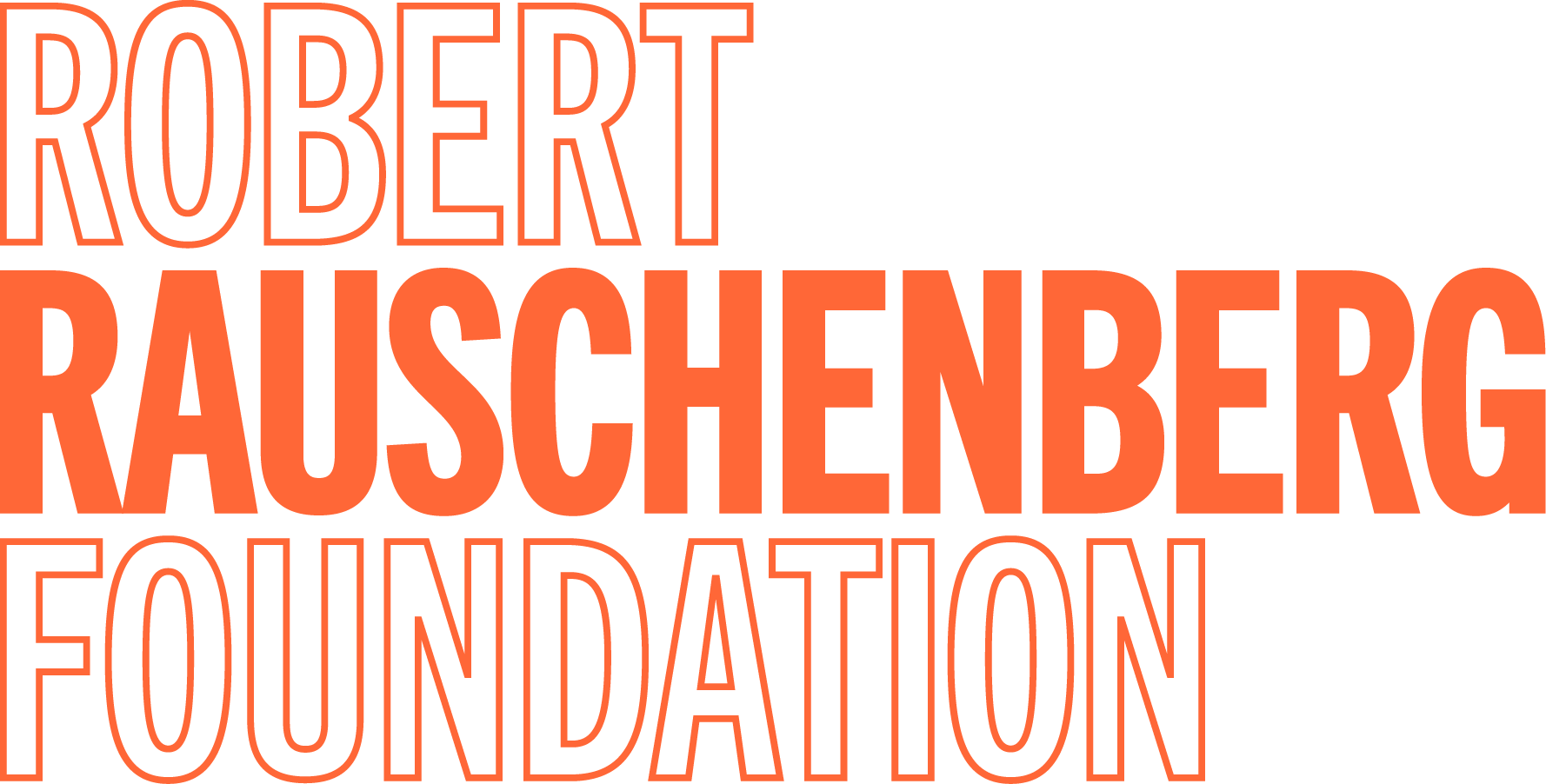

Stoned Moon Drawing, 1969

Stoned Moon

Stoned Moon Drawing, dated October 28, 1969, records Rauschenberg’s reflections on the Apollo 11 launch in July of that same year and the lithographic series it inspired. Embedded with the artist’s writings are photographs by Sidney Felsen and Malcolm Lubliner, who documented the working process at the innovative print studio Gemini G.E.L., Los Angeles, along with official images from NASA. The right side of the composition features the rising smoke plume of the rocket launch and the first boot prints on the moon’s surface. This work, together with the thirty-four Stoned Moon lithographs and the nineteen drawings and collages for the unpublished Stoned Moon Book, provides a singular account of the space program and humankind’s first lunar landing. In the collaged text, he remarks on the environs of Cape Canaveral, Florida, “highways built yesterday past ghost towns of technology abandoned with the haste and impatience of emergency surgery.” He intimates the anthropomorphizing sentiment, “My head said for the first time moon was going to have company and knew it.” Rauschenberg’s impressions contain a mixture of trepidation and wonder that conveys the technological and astronomical sublime.

Earth Day, 1970

Earth Day

In response to a massive oil spill off the coast of Southern California in 1969, Wisconsin Senator Gaylord Nelson initiated the idea of the first annual Earth Day on April 22, 1970. Soliciting support from Democratic and Republican leaders, Earth Day was conceived as a “national teach-in” to bring public awareness to the threat of global air and water pollution. What began as a grass-roots movement, with twenty million Americans participating, is now recognized as the launch of the environmental movement and observed in nearly 200 countries around the world.

Robert Rauschenberg designed the first Earth Day poster to benefit the American Environment Foundation in Washington, D.C., and it was published in an edition of 10,300 by Castelli Graphics, New York. Using the bald eagle as the dominant image, the artist symbolically placed the United States at the center of a global problem. Muted and muddy tones depicting environmental decay surround the national bird: polluted cities, contaminated waters, junkyards littered with debris, landscapes scarred by highways and deforestation, and the gorilla, another endangered animal. The safekeeping of the environment and the notion of individual responsibility for the welfare of life on earth was a longstanding concern of Rauschenberg, and this notion would inform his art and activism throughout his life. The poster designed for the inaugural Earth Day was one of many he would create to raise funds for the myriad social causes that were important to him.

A larger format lithograph, based on the original poster design and created as an edition of 50, was published by the American Environment Foundation and produced by Gemini G.E.L., Los Angeles.

Caryatid Cavalcade I / ROCI CHILE, 1985

Rauschenberg Overseas Culture Interchange (ROCI)

Rauschenberg’s belief in the power of art as a catalyst for positive social change was at the heart of his participation in numerous international projects in the 1970s and early 1980s, and which culminated between 1984 and 1991 with his Rauschenberg Overseas Culture Interchange (ROCI). ROCI (pronounced “Rocky,” the name of the artist’s pet turtle) was a tangible expression of Rauschenberg’s long-term commitment to human rights and to the freedom of artistic expression. Funded almost entirely by the artist, Rauschenberg traveled to countries around the world often where artistic experimentation had been suppressed, with the purpose of sparking a dialogue and achieving a mutual understanding through the creative process. Between 1985 and 1990, the project was realized in ten countries in the following order: Mexico, Chile, Venezuela, China, Tibet, Japan, Cuba, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), Germany, and Malaysia with a final exhibition held in 1991 at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Retroactive I, 1963

Retroactive I

Retroactive I (1963) belongs to the series of silkscreen paintings that Rauschenberg made between 1962 and 1964. His subject matter and commercial means of reproduction for these works led critics to identify him with Pop art. Unlike the one-to-one ratio he could achieve in the transfer drawings, the mechanically produced screens allowed him to transcribe his own photographs and images taken from the popular press onto a larger scale.

Monogram, 1955–59

Monogram

Monogram (1955–59) belongs to the series of Combines that Rauschenberg made between 1954 and 1964. A term coined by Rauschenberg, Combines merged aspects of painting and sculpture to become an entirely new artistic category. Art critic Leo Steinberg observed that the orientation of the Combines challenged the traditional concept of the picture plane as an extension of the viewers space, providing a window into another reality. Instead, Steinberg argued, a Combine is like a tabletop or bulletin board—a “receptor surface on which objects are scattered, on which data is entered.” Rauschenberg had seen the stuffed Angora goat—the focus of Monogram—in the window of a secondhand office-furniture store on Seventh Avenue in New York. Paying fifteen dollars toward the asking price of thirty-five dollars, Rauschenberg brought the goat to his studio, and before its completion in 1959, Monogram evolved through three states documented in drawings and photographs. The title is derived from the union of the goat and tire, which reminded Rauschenberg of the interweaving letters in a monogram.

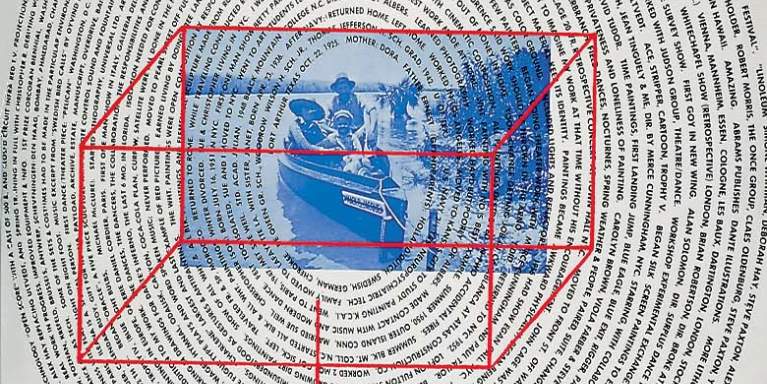

Autobiography, 1968

Autobiography

Rauschenberg’s monumental print Autobiography (1968) is a summation work that brings together the life and work of the then forty-three-year-old artist. Printed on three sheets of paper in an edition of 2,000, under the sponsorship of Marion Javits, wife of the U.S. Senator Jacob Javits, Autobiography is the first fine art print made on a billboard press. In each section, the artist’s personal history is woven together through a montage of indexical images—direct traces of the artist—such as photographs and X-rays, combined with references to places of personal importance and “found” imagery, including an umbrella and wheel, which are among Rauschenberg’s recurrent motifs. Upon its completion in January 1968, the sixteen-and-a-half-foot-tall, color, offset lithograph was immediately exhibited at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

Click here to view a transcription of the text printed on the center panel of Autobiography.

Mirage (Jammer), 1975

Mirage (Jammer)

Rauschenberg began the Jammer series in fall 1975, following a trip he had made the previous spring to Ahmadabad, India, a center of textile production. Bringing fabrics back to his studio in Captiva, Florida, the artist remarked on the beauty and luxury of the textiles and the sumptuousness of the colors, which appeared in marked contrast to the hardships he had observed in India: “the cruel combination of disease and starvation and poverty and mud and sand and yet it was all punctuated with maybe just that one piece of beautiful silk.” Mirage (1975), characteristic of the series, is made from sewn fabric; brightly colored and translucent silk, devoid of imagery that is loosely tacked to the wall, allowing gravity to determine its precise disposition. The name of the series is derived from “windjammer,” a type of sailboat, and the name “mirage” has a watery association. Mirage, referring to an optical illusion often perceived at sea, captures the fleeting sensibility of the piece.