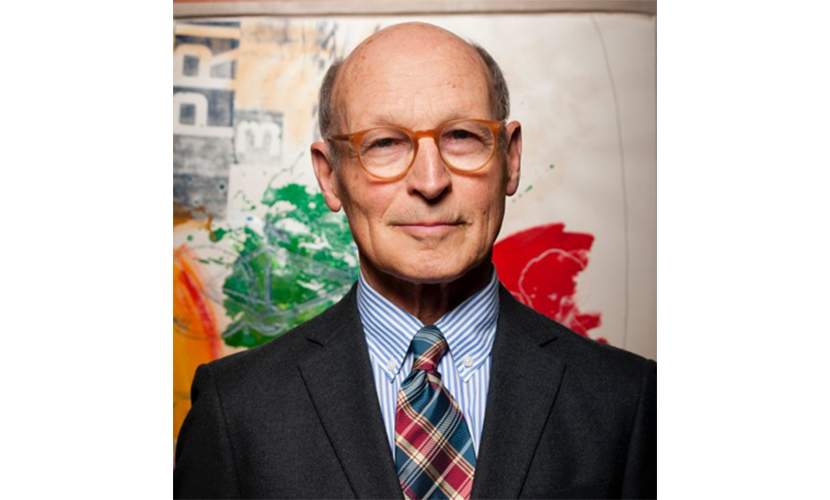

David White

David White was the curator for Rauschenberg from 1980 until the artist’s death in 2008. He is now senior curator at the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation and has overseen Rauschenberg exhibitions, publications, and projects over the last thirty years. Prior to joining Rauschenberg’s studio, White worked for both the Leo Castelli Gallery, New York, and the David Whitney Gallery, New York. Following the close of the gallery, White continued to work for Whitney who, as an independent curator, organized retrospective exhibitions of Jasper Johns, Cy Twombly, and the first exhibition of Andy Warhol’s portraits, all at the Whitney Museum of American Art. White is a graduate of the Rhode Island School of Design.

Excerpt from interview with David White by James L. McElhinney, 2013

White: That reminds me of a series that Rauschenberg did in the very early eighties, called the Salvage series [1983–85], where it came about because he was asked to design the sets and costumes for a Trisha Brown dance called Set and Reset [1983], I believe. It reminded me of what you were speaking of. In the costumes for the dancers, was a very gossamer white fabric, almost like wedding veil, a very open weave. The images were silkscreened on this fabric on a horizontal surface, a great big table. When the fabric that was to be used to make the costume was lifted off, there was this residue of ink that had gone through this very open costume fabric. Bob was not one to just waste something of that sort. That became the inspiration for what he called the Salvage series, because he salvaged this imagery and added to it. That became a body of paintings, and it was also a play on words because the edge of fabric is called a selvage, and Bob loved wordplay. So it was perfect.

McElhinney: Right, the lateral edge of the cloth is called the selvage. So the Salvage, selvage series. That’s very interesting, your observation about him being raised during the Depression and the impact that perhaps had on him. I think that he is of a generation that experienced a lot of hardship. I was reading somewhere that his clothing had been made of scraps at one point. His mom had made clothing from scraps of cloth, or something to that effect.

White: I’m not sure it was actually scraps of cloth, but he said that she could get more usable stuff out of a piece of fabric than anybody, when she was making his shirts and knew how to put the patterns for the arm and whatever. I think he was very impressed by that, eventually. And he spoke about it as an element of the enormous painting, the 1/4 Mile or 2 Furlong Piece [1981– 98] painting that he did. There’s a section of it which are actual shirts that have just been flattened and mounted on a backing and get presented on the wall, almost like clouds flying through the sky. But I’m sure in some sense, it’s a reference to his mother’s making of clothing when he was a young boy...

McElhinney: This waste-not, want-not ethic which came from a Depression childhood must have, in some way, informed his desire to be philanthropic. The idea of everything being useful, sharing, improving others through his means and hard-earned, well-deserved fortune.

White: I think very much so. The whole notion of Change, Inc. came about because he felt that tiny little bits of money might have helped enormously at a period when he was pretty much penniless and trying to become an artist in New York, and pay the rent, and eat. He never forgot that period of his life.