Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, New York, January 2023. Artworks by Rauschenberg, from left: Untitled (1986) and Around the Clock (Urban Bourbon) (1993); through doorway: Dusky Gaze (1969). Photo: Ron Amstutz

Inside 381 Lafayette: Rauschenberg’s New York Home and Studio Sixty Years On

2026 marks approximately sixty years since Robert Rauschenberg moved into his NoHo residence and studio, the last he would maintain in New York City and which today serves as the headquarters of the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation.

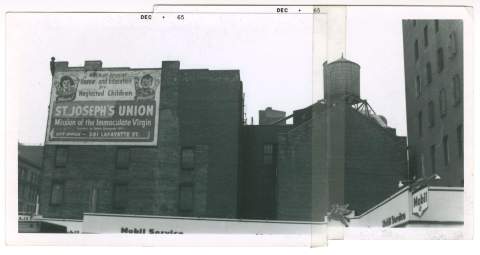

The purchase in 1965 of the five-story townhouse, constructed as a family home in the 19th century and later the site of the Mission of the Immaculate Virgin for the Protection of Homeless and Destitute Children, marked a turning point in Rauschenberg’s life and career. Following his first retrospective museum exhibition in 1963 at the Jewish Museum and a second retrospective at London’s Whitechapel Art Gallery in spring 1964, Rauschenberg stunned the art world by winning the International Grand Prize in Painting at the 1964 Venice Biennale.

Now sanctified as the winner of the “Olympics of Art,” Rauschenberg suddenly experienced a personally unprecedented sense of financial solvency and professional esteem. For over a decade, the artist had moved through a succession of cheap apartments and studio lofts scattered primarily across downtown Manhattan. His Fulton Street studio loft, located in a formerly industrial building near the East River, had no heat or running water, and featured a bathtub Rauschenberg fashioned from a tar-lined fish crate. From Fulton Street, he moved into Rachel Rosenthal’s former loft at Pearl Street, a floor above Jasper Johns’s studio and a short walk from the Coenties Slip, home to Agnes Martin, Robert Indiana, Ellsworth Kelly, James Rosenquist, and other artists, similarly living in abandoned lofts and cold-water flats. After the Pearl Street building was condemned, Rauschenberg and Johns both moved to studios in a building on nearby Front Street. As his son, Christopher, remarks in his Oral History, “He started out in a cold water place where he would have to go to parties so he could go somewhere where there was hot water and duck into the bathroom and take a shower.” His last residence before the Lafayette Street townhouse was an illegal loft in a commercial building on Broadway: a long, open space that tripled as home, studio, and occasional rehearsal space for members of the Judson Dance Theater. The acquisition of 381 Lafayette Street signified for Rauschenberg both space and stability - an opportunity to establish a permanent home and studio, as well as a welcoming, collaborative venue for artmaking and creative exchange.

In his work Master Minds: Portraits of Contemporary American Artists and Intellectuals, Richard Kostelanetz emphasizes the contrast between Rauschenberg’s new home and his previous digs, describing the Lafayette residence as “a Lower East Side palace, a five-story abandoned mission-orphanage that fulfills every New York’ artist’s dream of abundant space.” Writing not long after Rauschenberg purchased the building and converted it to his home and studio, the author provides an admiring account of the space and its use, enumerating the rooms on each ascending floor, from the studios in the chapel and high-ceilinged ground floor to a rehearsal area for performance on the fifth floor, under an accessible rooftop adorned with plants. In true Rauschenberg fashion, “most of the furniture came from the neighborhood second-hand stores, the stove is a relic from orphanage days, and the dishes do not match.”

By 1965, the Lafayette residence had already changed significantly since its construction over 100 years prior on what was then known as Lafayette Place, a chic residential area stretching from Great Jones to Astor Place. As the neighborhood grew increasingly commercial throughout the 19th century, 6 Lafayette Place was purchased by the Mission of the Immaculate Virgin, a children’s orphanage, for use as a convent, chapel, and administrative facility in tandem with the dormitory and school housed in the adjacent St. Joseph’s Home, constructed around 1880. In addition to renovating the façade in the Northern Renaissance Revival style, architect Benjamin E. Lowe extended the rear to construct a high-ceilinged chapel and increased the building’s height with the addition of a fifth floor.

At the time Rauschenberg acquired 381 Lafayette, the Mission had long since relocated all facilities but the administrative offices and convent to Staten Island. The St. Joseph’s Union building had been demolished in 1929, the chapel in the rear bisected and lot site transformed into a parking lot that remains today. With the help of the “loft king” Jack Klein, Rauschenberg purchased the building for $65,000 and spent $15,000 (Tomkins 220) on renovations before moving in the following year. Once deconsecrated, the luminous, two-story chapel became Rauschenberg’s primary studio and an iconic setting for artwork and events from Rauschenberg’s lifetime into the present. As partial payment for his services, Rauschenberg gifted Klein a work entitled Portrait of Jack Klein (1969); Rauschenberg later retitled the work Dusky Gaze and bought it back at auction. It is currently on display in the chapel as part of the Foundation’s Autobiography and Other Stories exhibition.

381 instantly became a locus of constant social, organizational, and artistic activity. Numerous artists lodged with Rauschenberg intermittently, including Brice Marden (also a studio assistant), Dorothea Rockburne, Mel Bochner, and Yvonne Rainer. As a result, the building earned the nickname “Milton’s Hilton” (Milton being Rauschenberg’s first name by birth). Still more artists, performers, musicians, curators, and gallerists passed through for dinners, parties, and conversation. “The kitchen was the main place,” the musician and frequent collaborator Dickie Landry remembers in his Oral History. “The giants of the art and music world at one time or another sat at this little table.”

Below is a selection of just a few notable events held at 381 Lafayette.

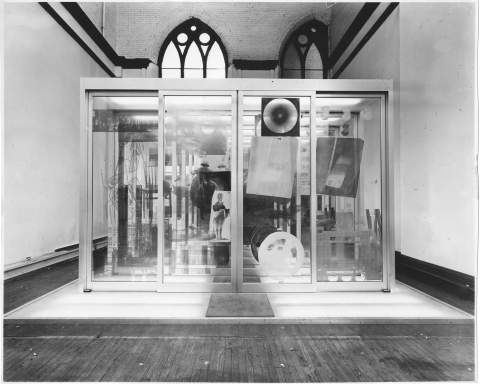

Experiments in Art and Technology

Not long after Rauschenberg moved into 381, the townhouse became the headquarters of the newly established Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.), co-founded by Rauschenberg, artist Robert Whitman, and engineers Billy Klüver and Fred Waldhauer to “to further the development of art and engineering and the interaction of art and engineering” (Certificate of Incorporation). On September 29, 1966, the organizers held a press conference in the chapel to announce 9 Evenings: Theatre & Engineering, a series of collaborative performances to be held at New York’s 69th Regiment Armory the following month. Composer John Cage, artist Öyvind Fahlström, choreographer Deborah Hay, Klüver, and Rauschenberg each spoke at the press conference. The chapel once again served E.A.T. the following year as the site of the Great Model Airplanes exhibition and benefit auction, organized by Christie’s and with works created for donation by the ONCE Group, June 6–8, 1967. Learn more about Rauschenberg and flight at the upcoming National Air and Space Museum exhibition, The Ascent of Rauschenberg: Reinventing the Art of Flight, opening July 1.

"Eye on Art"

In 1967, WCBS filmed Robert Rauschenberg in his studio for the television program Eye on Art. The segment, entitled “The Walls Come Tumbling Down,” captured Rauschenberg at work making solvent transfer drawings and screenprinting in the chapel, intercut with an interview at his kitchen table. Today, the broadcast and raw archival footage provide crucial documentation of Rauschenberg and artist Brice Marden, then his studio assistant, creating works in his Revolver series. An excerpt from “The Walls Come Tumbling Down” broadcast is currently on view in Robert Rauschenberg’s New York: Pictures from the Real World at the Museum of the City of New York, and Revolvers are currently on display at exhibitions at the Guggenheim and in Rauschenberg Sculpture at the Nasher Sculpture Center, Dallas.

"Kiki's Paris" Book Launch Party

In addition to hosting events promoting Rauschenberg’s own work and involvement in various organizations, 381 Lafayette was occasionally the site of parties to celebrate friends and their endeavors. On April 5, 1989, Rauschenberg and the publisher Harry N. Abrams held a “champagne toast in the spirit of Montparnasse in the 1920s” at 381 to celebrate the publication of Kiki’s Paris: Artists and Lovers 1900–1930 by Billy Klüver and Julie Martin, Rauschenberg’s longtime friends and former E.A.T. collaborators. Archival photographs and facsimiles documenting Montparnasse and the artists, writers, and models explored in the book lined the walls of Rauschenberg’s first-floor studio, and the extensive guest list included former models from the 1920s, who mingled with contemporary models in dresses silkscreened with images from the publication. Large, Warhol-inspired silkscreened pillows floated lazily throughout the space.

Artwork at the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

Rauschenberg moved his primary studio to Captiva, Florida, in 1970, but 381 Lafayette Street remained his curatorial and philanthropic home base until his death. Today it houses the headquarters of the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, founded by the artist in 1990. Since fall 2024, the Foundation has welcomed the public to view onsite exhibitions of Rauschenberg’s works on select Saturdays (to learn about future dates, join our mailing list). In honor of the centennial of Rauschenberg’s birth, Autobiography and Other Stories: Robert Rauschenberg in Words and Images explores Rauschenberg’s biography through works spanning over fifty years and representing his expansive use of diverse materials and techniques. Works such as the White Painting (1951), Page 6, Paragraph 2 (Short Stories) (2000), Mirthday Man II (Ceramic) (1998), and Eco-Echo IV (1992-1993) appear in dialogue with original writings on view from the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation Archives, each recently published in the collection I Don’t Think About Being Great: Selected Writings, edited by Francine Snyder.

381 Lafayette Street stands at the center of Robert Rauschenberg’s legacy: a monument indelibly imbued with the memory of Rauschenberg’s artistic and personal practices of experimentation, collaboration, and generosity, as well as the many individuals who filled its rooms. Though steeped in this rich history, the building is a dynamic, living space that will continue to change and thrive into the future as the permanent home of the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation.