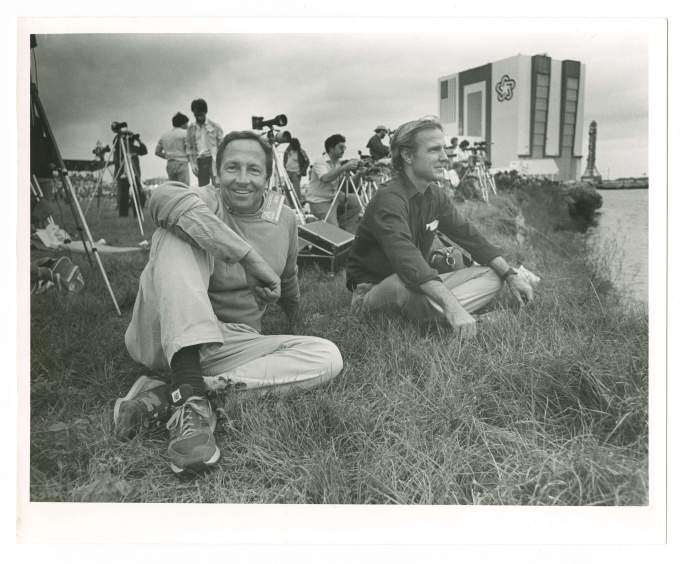

Rauschenberg and Terry Van Brunt viewing a NASA space shuttle launch at Cape Canaveral, circa 1983

All engines running. Liftoff!

An interview with NASA’s Lois Rosson on the launch of Apollo 11, NASA’s Artists Cooperation Program, and Robert Rauschenberg’s time at Cape Canaveral.

Did Apollo 12 leave a small drawing by Robert Rauschenberg on the surface of the moon? We may never know if the rumor about The Moon Museum (1969) - a ceramic chip to which six artists including Andy Warhol and Robert Rauschenberg contributed and which was allegedly attached to the leg of a lunar lander that year - is true. What we do know, however, is that Rauschenberg was one of the few artists invited by NASA to witness the launch of Apollo 11 as part of the NASA Artists Cooperation Program. His interest in space exploration predated the 1969 event, but the launch fueled his imagination and inspired many artworks. More than 50 years later, we sat down with NASA historian Lois Rosson to discuss the program, which also included artists such as Annie Leibovitz, Norman Rockwell, and Andy Warhol, and for which Laurie Anderson served as the agency’s first artist-in-residence in 2002.

Rosson has carved out a unique space at the intersection of art, science, and public history. With a background in fine art and experience in academia and archival work, she now documents NASA’s institutional memory and explores the agency’s surprising ties to artists. In this interview, Rosson shares how she arrived at NASA, the origins and impact of the NASA Artists Cooperation Program, and what made Rauschenberg’s participation special. We thank her for her time and expertise.

RRF: Lois, thank you so much for agreeing to share your expertise. How would you describe your path to becoming a historian at NASA, including how your background in fine art led you there?

Rosson: It was an indirect trajectory. I’m a historian in the NASA History Office, which exists partially because NASA has a congressional mandate to make its work legible to the taxpaying public. I started at NASA in 2013 as an intern, right out of undergrad, with a background in fine art. I was initially hired to do graphic design for the Tech Transfer Office. But what really hooked me was discovering NASA’s robust archives—especially at Ames [Research Center in Mountain View, CA], where I found technical illustrations commissioned for different spaceflight missions as well as artwork from the NASA Artists Cooperation Program. The first day of my internship I was wandering around and spotted a Rauschenberg lithograph in a hallway. I encountered a surprising amount of artwork at NASA, which inspired a lot of questions about the agency’s function as a cultural institution. The experience motivated me to go to graduate school and get a PhD in the history of science, focusing on how a scientific institution like NASA came to commission artwork in the 20th century. After a couple of postdocs, I joined the NASA History Office in April 2023, and now my day job is writing the kinds of histories I once studied as a grad student.

RRF: What does your day-to-day work look like in the NASA History Office?

Rosson: Every day is different, but the big constants are conducting oral histories and producing historical reports and monographs. Oral histories are a great way to capture institutional memory—since I started, I’ve probably done thirty or forty of them. These are transcribed and made freely available online, so anyone can use them as raw material for research. We also publish single-subject historical monographs, written by professional historians, which are also available online, free of charge.

RRF: We’re here today because Rauschenberg was one of the few artists invited to witness the Apollo 11 launch, as part of the NASA Artists Cooperation Program. Tell us about this unique program.

Rosson: The NASA Artists Cooperation Program started under James Webb, NASA’s administrator in the early 1960s. Webb was moved by an oil portrait of astronaut Alan Shepard that he felt captured something beyond what a photograph could, and was interested in commissioning portraits of other members of the early astronaut corps. These portraits never came to pass, but it planted a kernel of interest in using art as a public outreach tool. At a time when human space flight was far from guaranteed and the Apollo program was characterized as overly expensive, Webb—who wasn’t a scientist but more of a Cold War “hearts and minds” strategist—saw art as a way to communicate the cultural significance of NASA’s work. He pushed for an art program, reaching out to the National Gallery of Art and borrowing their Curator of Painting Hereward Lester Cooke, to help launch it. The association with the National Gallery of Art gave the program legitimacy, and insulated it from accusations of being sympathetic to the communist ideologies popular in the art world in the 1960s. The backdrop of Cold War politics present at the time made this a pressing issue.

One thing that’s important to remember about the NASA Artist’s Cooperation Program is that it was created in 1963 and predated the National Endowment for the Arts. It played an important role in showcasing how government support for the arts could lead to positive outcomes. The art initially produced for the NASA Artists Cooperation Program culminated in a 1965 exhibition at the National Gallery of Art, which received overwhelmingly positive reviews. These reviews were later cited in Congressional discussions that led to the creation of the NEA, showing how NASA’s art program influenced broader cultural policy.The program helped NASA emphasize the cultural and symbolic value of space exploration,not just its scientific or technological achievements. This proved to be a valuable model in the 1960s.

RRF: Under James Webb, the program’s inaugural Director was James Dean. I believe you met him?

Rosson: Yes. When I was doing my doctoral research, I spent a year at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum. The museum’s first art curator was James Dean, who joined Air and Space after wrapping up his tenure with the NASA Art Program. He had tons of experience and graciously offered many stories for my research. What’s not as well-known about him is that he also was a really talented watercolorist. He actually had a studio space out at the Torpedo Factory in Alexandria. And he told me that visitors would always poke their heads into his studio and ask “are you the James Dean?” [laughter]. Eventually, he had to get a little plaque that said “the other James Dean.”

RRF: How did James Webb, James Dean, and Hereward Lester Cooke select the participating artists?

Rosson: They first looked to the U.S. Air Force Art Program. The structure of the NASA Artists Cooperation Program resembled earlier examples of state sponsored military painting. The Air Force Art Program was the NASA Art Program’s closest sibling, emerging out of an impulse to commemorate the aircraft that helped the United States win the Second World War. So a lot of the painters involved in the Air Force program were depicting airplanes in flight–I think of them as akin to oil paintings of thoroughbreds. A lot of the participants in the Air Force Art Program were also servicemen. This first roster went on to work in the NASA Artists Cooperation Program; it was seven artists, including Lamar Dodd, Mitchell Jamieson, and Paul Calle, who went on to do a really famous series of postage stamps of the Apollo 11 astronauts for the NASA Artists Cooperation Program. Robert McCall was perhaps the one who found the most success: he created promotional artwork for the 1970 movie “Tora! Tora! Tora!” and then he did all of the artwork for “2001: A Space Odyssey.” He also created the large mural inside of the Air and Space Museum’s DC location.

RRF: So how did NASA evolve from this first cohort of artists to a program that would include Rauschenberg?

Rosson: Quite the progression, isn’t it? After the first cohort, their decision-making process is not as well documented. We do know, however, that Hereward Lester Cooke invited a broader roster of artists to participate. Salvador Dalí was invited, and though there was initial interest, the correspondence eventually dropped off. Andrew Wyeth, who was at the time one of the most famous painters in America, declined an invitation to join the program, but his son Jamie Wyeth did participate. Thomas Hart Benton was also invited, but declined because of moral qualms about a government sponsored space program. Rauschenberg had a pretty pronounced interest in flight, so I think he made a lot of sense to include.

The Artist’s Cooperation Program really peaked during Project Apollo. By 1974, as manned space flight slowed down, so did efforts to document it. There was a version of the art program that was revived in the 1980s to coincide with the shuttle program that was smaller in scale but invited several well-known artists to participate, like Annie Leibowitz and Chakaia Booker.

RRF: What was the program like for artists? What do we know of Rauschenberg’s experience at the Apollo 11 launch?

Rosson: A lot of them stayed at motels around Cocoa beach. Not all artists working with NASA went to Kennedy. Mitchell Jamieson, for example, went to Pearl Harbor to go sit on an aircraft carrier that was recovering one of the Mercury capsules out of the ocean. All artists received NASA badges and were invited on some “field trips” to get a sense of the site and how it functions.

A lot of the participating artists documented life at Kennedy with sweet, simple scenes; for example, Jamie Wyeth’s “Gemini Launch Pad” shows a bicycle propped up on the side of a launch gantry. There were a lot of bicycles around -- that was one of the ways that the scientists and engineers at Kennedy were getting around, and Wyeth was tickled by this very rudimentary technology put up against this structure that's now used as a visual shorthand for the future. Going back to Rauschenberg's lithograph at Ames: one of the first aspects that interested me in his work was his attention to the natural landscapes of southern Florida.

RRF: Of course, Rauschenberg had a long relationship with Florida, especially the island of Captiva and its fauna and flora. He was also interested in environmentalism. Was that conversation present at the time?

Rosson: The short answer is “kind of.” Something that gets lost in the memory of Apollo 11, in part because it was fundamentally successful, is that it wasn't obvious that it was going to be successful. Right up until the Moon landing actually happened, most people were not sure it was going to work. One of my favorite Space Age artifacts is the alternate speech that Richard Nixon prepared in case the Apollo 11 astronauts perished on the surface of the Moon. He adapted the speech from naval protocols in place for when sailors are lost at sea, because we wouldn't have been able to recover the bodies. I think the speech really speaks to the fact that we didn't really know what the outcome of the mission was going to be.

The 1960s and the space program also coincided with one of the biggest global movements that progressivism has ever seen. Campus protests, the anti-war movement and the early environmentalist movement were receiving a lot of attention. A lot of people were critical of NASA as a function of the same military industrial complex that was fueling the war in Vietnam. Other groups were frustrated with NASA because it cost $25 billion at a time when the United States was attempting to engineer a social safety net. Civil rights activist Ralph Abernathy famously brought a mule train to Cape Canaveral to signal the fact that African Americans in the United States had been promised reparations for the experience of slavery over and over again, and yet the country still prioritized goals with no clear benefit for poor communities. All this criticism was present at the time of Rauschenberg’s visit for the Apollo 11 launch. We don't necessarily remember it now, because now we describe Apollo 11 as one of the most monumental successes of the 20th century, but not everyone agreed it was a good idea.

The environmental impact of space activities is something we’re just starting to contend with. Today, we know that rocket fuel contaminates the ocean. We also know that accelerated launch schedules can be very disruptive to local ecology; sonically, they impact Florida’s wetlands. Those types of critiques are a little bit more recent, but given Rauschenberg’s interest in Florida’s ecology, it's interesting to speculate whether this was something on his radar.

RRF: Rauschenberg designed the poster for the first Earth Day in 1970. He understood the power of strong iconography to unite a movement. How did this manifest at the NASA Artist Cooperation Program?

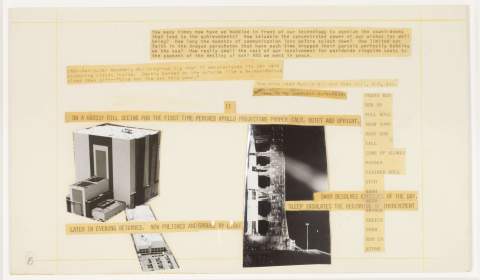

Rosson: The purpose of the NASA Artist Cooperation Program was to cut through the glut of images. Apollo was over-exposed from a photography standpoint. The artwork produced for the NASA Artist’s Cooperation Program was designed to introduce images with more cultural weight than press photography or technical documentation. What Webb and NASA were looking for were artists to come in and cohere these images into something that imbued with meaning. That’s exactly what Robert Rauschenberg did with his Stoned Moon Book (1970)-- a combination of photography with drawings, paintings, and diary entries [the text derives from Rauschenberg in dialogue with curator Henry Hopkins]. I remember seeing in my research that NASA administrators were not thrilled about Rauschenberg calling his series Stoned Moon. And sometimes,in NASA public affairs coverage, the series has been renamed “Stone Moon,” instead of “Stoned Moon,” which does still work in the context of lithography! So that's something to look out for. [laughter]