Robert Whitman

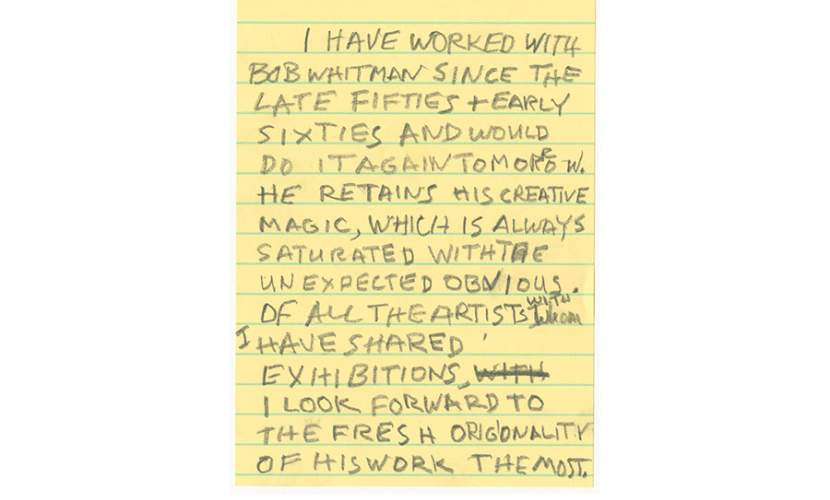

Robert Whitman was a principal figure in the Happenings of the late 1950s through the early 1960s. He completed his undergraduate education in 1957 at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, New Jersey, then a hotbed of avant-garde activity. There he connected with faculty members Allan Kaprow and George Brecht, fellow student Lucas Samaras, and occasional instructor George Segal. Through Kaprow, Whitman met Rauschenberg around 1957 and struck up an enduring friendship. Among Whitman’s iconic Happenings are American Moon (1960), Flower (1963), and Prune Flat (1965). He contributed Nighttime Sky (1965) to the First New York Theater Rally (1965), and in 1966, together with Rauschenberg and engineers Billy Klüver and Fred Waldhauer, he cofounded Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.). E.A.T. fostered collaborations between artists and engineers, which had initially developed out of preparations for 9 Evenings: Theatre & Engineering that same year. The organization fostered collaborations between artists and engineers, having developed out of preparations that year for 9 Evenings. For the series Rauschenberg and Whitman both created performances integrating technology. Whitman made pioneering works that incorporated film into sculptural constructions, including Shower (1964), which Rauschenberg acquired for his own collection. His work Swim (2015) was a multisensory experience designed for both blind and sighted audiences. Whitman continued to work with performance and the moving image until his death in 2024 at the age of 88.

Excerpt from interview with Robert Whitman by Alessandra Nicifero, 2014

Whitman: It was interesting to me that Bob had that relationship with other performers and later on of course making his own stuff. Sometimes I hate it that somebody does stuff that’s so fabulous. Pelican [1963] is one of the great pieces and Open Score [1966] is one of the great pieces. Those particular pieces, it’s just my bias, but I think they are so strong and uncluttered and perfect.

[ . . . ]

Nicifero: So you mentioned Open Score. That is part of the great 9 Evenings[: Theatre & Engineering] at the [69th Regiment] Armory [New York]. Can you talk about—

Whitman: I could talk about that piece in particular. I’ll describe it. I’m sure that when this is all done, you’ll have all this material and film anyway.

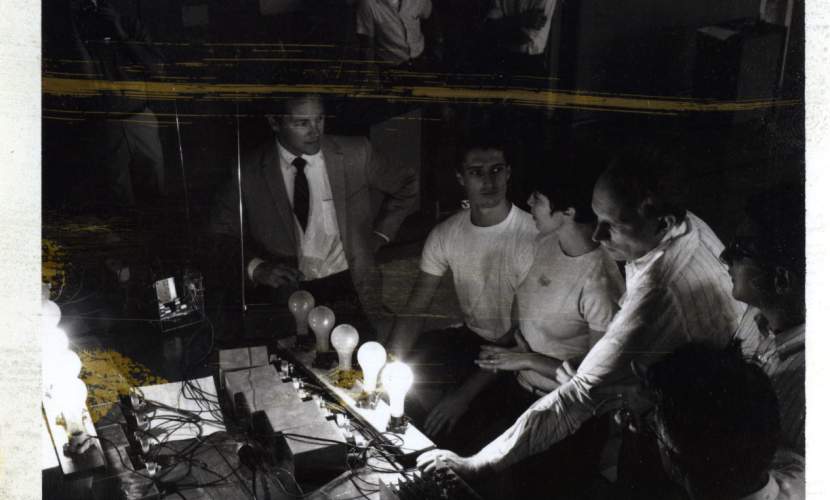

It’s a tennis game. First, people come out and I think they set up the net and stand there because they have to hold the net taut. You couldn’t just mount the net on the floor of the armory where it took place. Let’s see. Each time the ball was hit, the sound of the ball was amplified through the space and the speakers. One can talk about the technology, but it’s just too boring to talk about that stuff.

So you heard the cosmic pock of the sound of the ball hitting the racket. And each time the sound came, a light went off, until the space was in complete darkness. I think the sound continued—I’m not sure—for a while. In the dark, you heard people say their names. There was a rustling sound of a lot of people in the dark. You couldn’t see the people until they were projected—he had gotten a hold of infrared video cameras and projected images of this crowd of people who were like ghosts, appearing on the floor in front of the audience. They made gestures that were cued by lights that they could see, that were behind the audience. They made simple gestures like embrace your neighbor, wave, or something simple like that. And then somehow they got off the floor.

For the second night, the second performance—he didn’t have it on the first one—he appears and picks up a burlap bag on the side in which Simone [Forti] is singing this fabulous song. Somehow she filled that space which had lousy acoustics, but it worked and you could hear the words very well. It was really great. That was almost like the end of the piece. Terrific.

Nicifero: How was the organization of the 9 Evenings? How was working and getting ready for the big event?

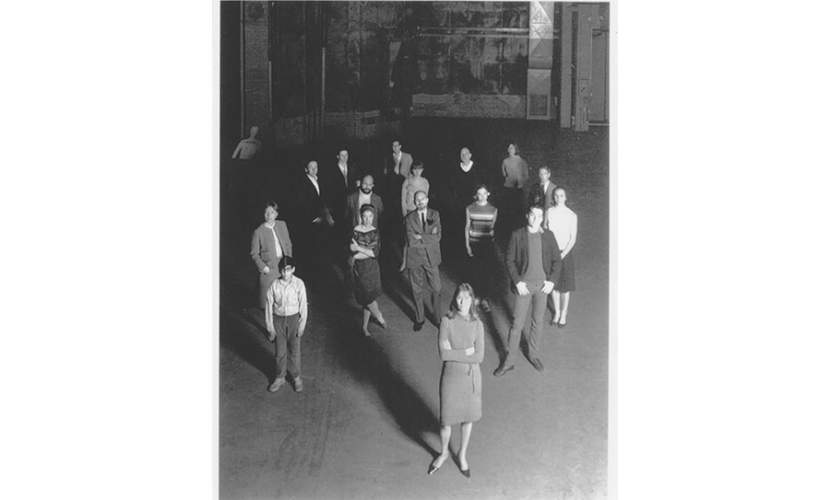

Whitman: I would have to say that it was completely insane. No rational person would have thought of doing this, but Billy [Klüver] just proceeded ahead as though there were no obstacles and it was easy. Letting, letting his fantasy come to fruition—and everybody else participated in this. It was mad. Everybody was under amazing stress. I don’t think anybody really had a clear idea of what they were doing except Bob’s piece, of course, and John [Cage]’s piece. They were all tightly composed.

Having seen a lot of the material recently, five or six years ago, the thing that stands out is how many people participated. It must have been hundreds almost. I don’t know how many people participated, but I get the impression that hundreds of people, engineers and artists and friends, just jumped in and participated without getting paid. Amazing generosity and focus on the part of these people, in spite of all the attention. Only maybe the artists and some of the engineers were aware of the dangers of the technology that was being used—other people just went along with it. It’s hard to understand. Looking at the videos now, it’s amazing how this got done. The amount of work is huge because a lot of the pieces were quite complex.