Lawrence Voytek

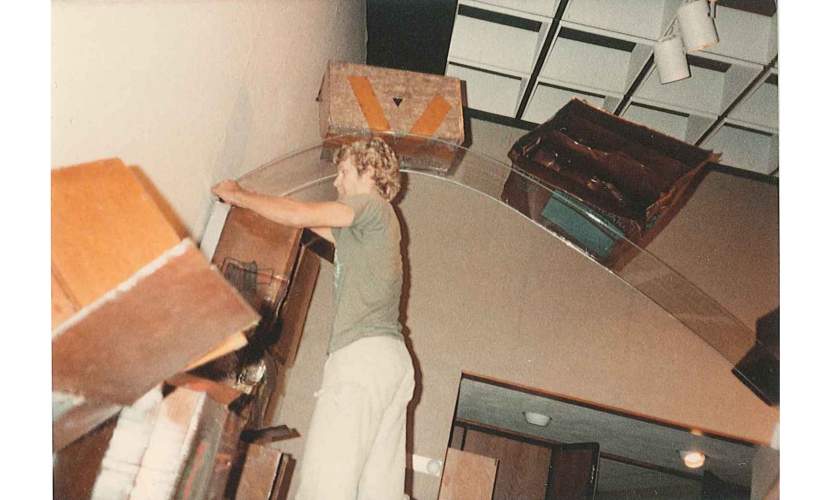

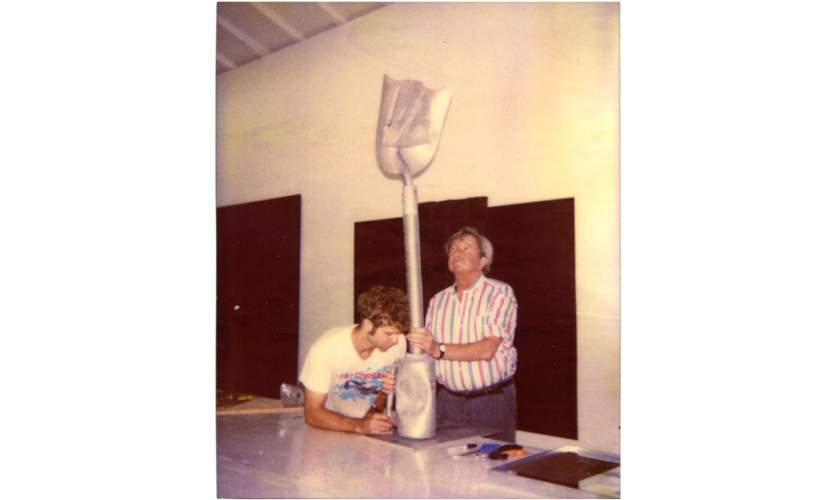

Graduating with a bachelor of fine arts in sculpture from Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, in 1982, Lawrence Voytek was hired that same year to work as a fine art fabricator in Rauschenberg’s Captiva Island studio in Florida. With only a welder on a dirt floor and no walls, Voytek helped build and establish an extensive private workshop on the property. A versatile problem solver, he was instrumental in enabling Rauschenberg to overcome various technical challenges by using engineering and welding expertise to allow the artist to explore a wide range of material possibilities. As a vital member of the studio staff, Voytek and Rauschenberg remained friends until the artist’s death in 2008.

Excerpt from Interview with Lawrence Voytek by Donald Saff, 2016

Saff: Did Bob ever discuss the images that he’d—?

Voytek: Never. Bob grabbed images all the time. And Bob—and this is kind of a funny—Bob was such a visual thinker. When I first started working for Bob I wanted to try to understand where this guy was coming from, how he became so brilliant. And Bob—I think you’ve talked about this in things that I’ve read, about the way Bob talked and the way that Bob played around with words and stuff. Bob early on explained—they say dyslexic—Bob said that he had a problem reading. And when I was working with Bob, Bob said that when he read stuff, he had visions of what the words were when he read them. And if he had something in front of him and he started to read it, he would confuse himself with the possible ways that this word could be. And so he would say, “The rain in Spain.” The reign might be king, it could be—rain, Spain, falls merrily on the plain—it could be an airplane. And he said that all these visions would be happening for him to choose the right word, he’d have to keep going back to try to follow where he’s going.

So his visions would slow him down when he would read. And he had feelings about visions where you say “dog,” you might think of Lassie whenever you hear the word dog. Bob had visions and feelings. And so when he’d look through pictures, he would have feelings. A picture is worth a thousand words and his editing of or combining of images was intoxicating to him in some ways. And if you talked to him, he would give you this movie trailer of how he was explaining what he was talking about. The tangents were like his artwork, where the connections were so hard to follow where it’s coming from and where it was going.

Saff: Once in a car with Bob, we were in New York City, and he looked out the window and said that New York was a movie without a script. And I think he meant by that it was all open-ended and that words were layered. Syntax was not strict, word meanings were multiple, as you described.

[ . . . ]

Voytek: Also Bob would always say, “Don’t talk about the magic. Don’t talk about [how we work]. Don’t tell people what things are because if you explain something to somebody, then they’re going to stop looking. If they read the damn label on the wall, they’re not going to look at it. They think that’s what it is.”

Saff: Well and that’s why he didn’t want to describe techniques with anybody. He didn’t want to discuss—if someone asked him how was that done, he’d deflect immediately because he felt that that had a deleterious effect on their ability to see the content of the work.

Voytek: He was really intense about making the work as something that visually, it was really well done. But he was also into what wasn’t retinal, what wasn’t seen, where it would make the jump into something more important than just an object. It had concepts that were beyond what objects just are.