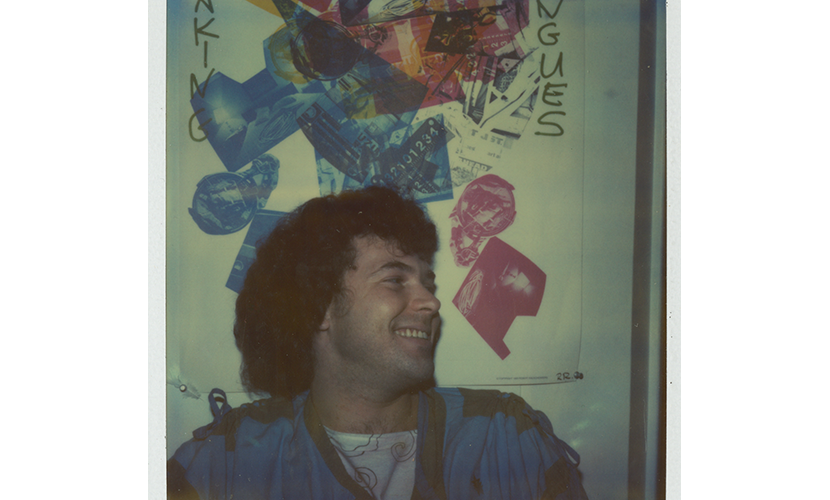

Larry Wright

Larry Wright is a master printer and former professor at the School of Visual Arts, New York. He is the principal of Larry B. Wright Art Productions, New York, a fine art printing and fabrication studio, which has worked with well-known artists and gallerists such as Leo Castelli, Larry Poons, Rauschenberg, Art Spiegelman, and Andy Warhol. In addition to a selection of Rauschenberg’s print projects, the studio also facilitated collaborations between Rauschenberg and choreographer Trisha Brown. In the late 1970s Wright worked in Rauschenberg’s studio in Captiva, Florida, helping to set up the artist’s photography and screen-printing workspace.

Excerpt from Interview with Larry Wright by Sara Sinclair and Christine Frohnert, 2015

In looking at the works from the 1978 Works from Captiva catalogue for the show at the Vancouver Art Museum, some of the works that we didn’t have out here today are in the catalogue, one of them being Half A Grandstand, which is aptly named because it is very big. It’s six door skins, horizontally arranged—three on the top, three along the bottom on their sides—so it’s about 21 feet long, something like that probably, by about 6 or 7 feet high. Half A Grandstand was the product of quite a night. Bob used to joke—there was a lot of drinking going on as we were working, but it was just part of the background, part of the wallpaper. But there were occasionally nights that stood out, in which case we’d meet up at the Beach House in the morning and Bob would say something like, “It was very drunk out last night.” This was one of those nights. Half A Grandstand was truly a party. We were printing and we were painting and we were gluing and we were making stuff and Bob was just—he took everything off of my worktable. He put my ruler in it, he took my towel, my rag. I would work with something and he’d just take it and boom, it was in the artwork. It was kind of a snapshot of the free-for-all that the work environment was or at best could be.

He was just brilliant and when the mood—when the spirit was upon him as they say, there was just no stopping him. It was contagious and everybody—myself and anybody else in the room—would get caught up in it. The Half A Grandstand piece, it does have lots of stuff in it that wasn’t intended. With that piece, there was very little planning. We knew we were going to make something real big and real horizontal. [Laughs] But it really sort of just birthed in front of us.

As I said before Bob was really—he was fast. It was amazing to watch him work. He had this intrinsic talent that was so much a part of him. You’d be speaking with him and he’d be telling you something and he’d put three or four things on the table and you’d look at him and just say, “Shit, that’s beautiful. The arrangement of what you just did with the saltshaker and that cup. And look at the napkin.” He just would do things—he would elevate any three-dimensional situation into art. To watch him work was truly electrifying because he made connections between things, among things, that all just seemed perfect. You put two things next to one another that are unrelated, but Bob would see the connectivity. It’s like some savant pool player who, you see the pool table and the cues, he sees dotted lines that go to the corner pockets. Bob was like that. He would see something the rest of us didn’t see.

You’d be walking down the street with him and you’re all looking at the same stuff, you’re in Manhattan. But Bob would see something. He’d just sort of go over and take a picture of some little detail—a standpipe in front of a building—and it was beautiful or suddenly it became like an animal or suddenly it became a person’s figure of some kind. The thing about photography with him was that you were a little bit able to know what it was like to be inside of his head. You’d see the results of it, but especially with the photographs, the things that interested him—the sort of imperfection and stuff that he was attracted to, which really make things interesting—would call to him in a way that other people couldn’t hear. [Laughs]

So, the Half A Grandstand—I’m going to look down because I have the catalogue here. Yes, we’ve got our dishtowel. We’ve got my two napkins because we ate something. He’s got an image—an anatomical image—in our beer flats, we had anatomical images of body parts and stuff—so he has a kind of medical drawing of a leg and then he has all of these—from the plants and fruits box—he has grapes. Actually the leg is supposed to be Italy and they’re stomping on grapes, which is wine. So that all relates. That’s a whole little highlighted panel that sits very bright in the middle of a yellow rectangle on the far left side of Half A Grandstand and it’s a little ode to the muse, to the grape. This is a little parable. A little story.