1960-69

1963

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, acquires the illustrations for Dante’s Inferno (1958–60) through an anonymous gift from a donor who had purchased them for $30,000 from Leo Castelli, New York. Under the auspices of the International Council of the Museum of Modern Art, the drawings will be exhibited in museums throughout Europe over the next two years and throughout the United States from 1966 to 1968.

In collaboration with engineer Harold Hodges, makes Dry Cell (1963), an interactive sculpture where motion is voice activated. Viewers are encouraged to speak into a small microphone that is wired to a motor that in turn causes a small, irregularly shaped piece of metal to spin. The face of the work is Plexiglas onto which is screened an image of the army helicopter that also appears in many of the silkscreen paintings, including Kite (1963).

January: Foundation for Contemporary Performance Arts, New York, founded to support performances by avant-garde artists and composers. Directors include John Cage, Jasper Johns, Elaine de Kooning, and other artists.

February 1–16 and February 20–March 9: Consecutive solo exhibitions Rauschenberg: Première Exposition (Oeuvres 1954–1961) and Rauschenberg: Seconde Exposition (Oeuvres 1962–1963), Galerie Ileana Sonnabend, Paris. Première Exposition includes Combines Charlene (1954), Hymnal (1955), Monogram (1955–59), Gloria (1956), Memorandum of Bids (1956), Rhyme (1956), Untitled (1956), Gift for Ileana (1956–59), Blue Collage (now Collage with Blue, 1957), Collage with Cuff (1957), Bypass (1959), and Dylaby (1962). Seconde Exposition includes silkscreen paintings: Almanac (1962), Brace (1962), Calendar (1962), Crocus (1962), Echo (1962), Exile (1962), Glider (1962), Payload (1962), Shortstop (1962), Vault (1962), and four untitled paintings (all 1963). Man Ray attends opening. Critic Pierre Schneider describes the work as “combining ‘raw’ objects (radio sets, stuffed goats, keys, neckties, etc.) with paint as sweetly tasty as the Good Humor man’s goodies. There they are, the erstwhile ruffians of mass production with pretty pigments round their necks, like repentant delinquents meekly wearing the choir boy’s surplice.”1

February 3–28: Exhibits silkscreen paintings—Cove, Tadpole, Express, Junction, and Dry Run (all 1963)—at Beaumont-May Gallery, Hopkins Center, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire, where he is a visiting artist for the spring semester.

February 25–March 2: Participates in Exhibition for the Benefit of the Foundation for Contemporary Performance Arts, Allan Stone Gallery, New York. Contributes Overcast II (1962), a black-and-white silkscreen painting.

March 14–June 2: Participates in Six Painters and the Object, curated by Lawrence Alloway, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Exhibits Untitled (now Collection, 1954), Factum II (1957), Migration (1959), Overcast I (1962), Overcast II (1962), and Junction (1963). His inclusion in the exhibition, along with artists Jim Dine, Johns, Roy Lichtenstein, James Rosenquist, and Andy Warhol, led critics to identify Rauschenberg with Pop art, an affiliation that he rejected.

March 31–May 12: First retrospective museum exhibition, Robert Rauschenberg, organized by Alan Solomon, director of the Jewish Museum, New York. The show consists of fifty-five works spanning his entire career to date. Rauschenberg creates the exhibition poster, an offset lithograph which is an adaptation of the lithograph Rival (1963). The exhibition marks the first occasion for a museum to present the work of a post–World War II artist from New York and initiates the Jewish Museum’s contemporary art program, which will thrive throughout the rest of the decade. Victor and Sally Ganz, prominent collectors, purchase Winter Pool (1959) from Leo Castelli, New York, the day after the opening.

Spring: Creates “Random Order,” published in Location, a short-lived New York–based magazine. The work consists of a full-page reproduction of silkscreen painting Sundog (1962), a two-page collage of Rauschenberg’s own photographs and handwritten text, a full-page reproduction of silkscreen painting Renascence (1962), and a full-page reproduction of a photograph by Rauschenberg labeled “View from the artist’s studio.” The project illustrates Rauschenberg’s interest in finding connections among the disparate events of daily life or, as he writes, locating the “random order that cannot be described as accidental.”2

April 18–June 2: Participates in The Popular Image, Washington Gallery of Modern Art, Washington, D.C. Exhibits Backwash (1959), Black Market (1961), Cove (1963), and Express (1963).

April 28, 29: An Evening of Dance, Judson Memorial Church, New York, a program for which Rauschenberg serves as lighting director and designs the flyer. This is the first event to use the name Judson Dance Theater in its promotional materials. Yvonne Rainer’s Terrain premieres.

May 3–June 10: Participates in Schrift en beeld [Art and Writing], Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam. Exhibits a Combine painting, Bypass (1959), a lithograph, Urban (1962), and a transfer drawing, Comment Drawing (1962). The exhibition will travel to Staatliche Kunsthalle, Baden-Baden.

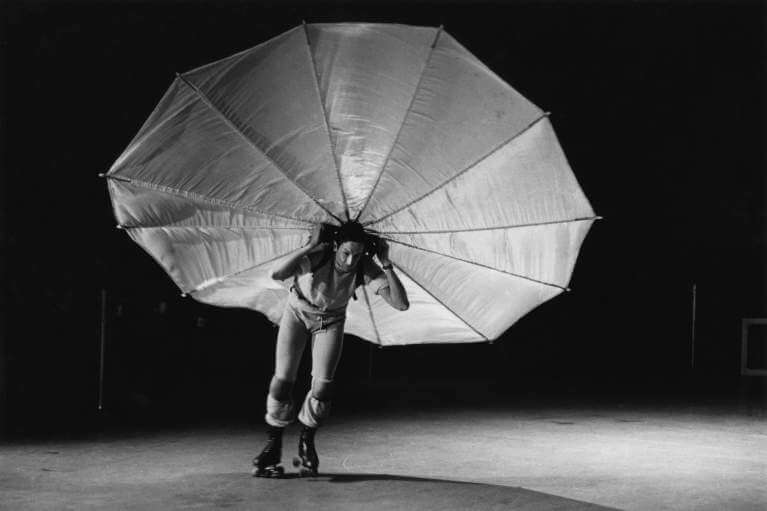

May 9: Premiere of Pelican, the first performance choreographed by Rauschenberg, Concert of Dance Number Five, an evening of performances by Judson Dance Theater, Pop Art Festival, Washington, D.C. (Rauschenberg does the lighting for all events). The festival of theater, dance, and film is organized by curator Alice Denney in conjunction with the exhibition The Popular Image, Washington Gallery of Modern Art, Washington, D.C. In the performance, which takes place at America on Wheels, a roller-skating rink, Rauschenberg and artist Per Olof Ultvedt (replaced by Alex Hay in later performances), wear circular structures of stretched parachute silk on their backs and propel themselves on roller skates while Carolyn Brown, a member of Merce Cunningham Dance Company, dances on pointe between them. The accompanying sound track, created by Rauschenberg, is a collage of sounds ranging from radio, television, and film to music by George Frideric Handel and Franz Joseph Haydn.

[June]: Begins using color in silkscreen paintings, occasionally using some of the same images previously included in the black-and-white silkscreen paintings. Rauschenberg quickly abandons attempts to replicate realistic color and to maintain exact color registration, choosing instead to highlight a handmade quality.

June 9: Accident (1963) wins Grand Prize, 5th International Exhibition of Graphic Art, Moderna Galerija, Ljubljana, Yugoslavia. This is the first time the award goes to an American. The title of the print, published by Universal Limited Art Editions (ULAE), West Islip, New York, in an edition of twenty-nine, derives from the breaking of the lithography stones twice during the printing. When the second stone broke, Rauschenberg decides that he wants to go ahead with the printing; the imprint of the crack and broken chips of stone at the bottom of the print documents the event. The print and award establish ULAE as a preeminent print workshop.

June 10: Rauschenberg performs his Prestidigitator Extraordinary, a solo work, at the Pocket Follies, a benefit organized by James Waring for the Foundation for the Contemporary Performance Arts, Pocket Theater, New York.

July 17: Premiere of Merce Cunningham Dance Company’s Field Dances, Royce Hall, University of California, Los Angeles, for which Rauschenberg designed the lighting and costumes (a harlequin outfit and nightdresses).

July 24: Premiere of Merce Cunningham Dance Company’s Story, Royce Hall, University of California, Los Angeles, for which Rauschenberg designs the costumes, lighting, and set. The costume designs reflect Cunningham’s “open form” technique, realized in Story, in which dancers spontaneously choose to perform a sequence of material from a carefully rehearsed selection. At any moment, dancers may don any of thirty-five items (including shirts, pants, sweaters, dresses, a football player’s shoulder pads, and a gas mask) located in bags in the wings. For each performance of Story during the 1964 world tour, Rauschenberg will design a new set, using existing features of the performance space and objects found locally. As Rauschenberg later explains, “Neither dancers nor choreographers ever knew what to expect until curtain.”3

Early October: Father dies of a heart attack. Rauschenberg returns to Louisiana for the funeral.

October 26–November 21: Solo exhibition of color silkscreen paintings, Leo Castelli, New York. Exhibits Archive, Bicycle, Die Hard, Overdrive, Shaftway, and Windward (all 1963).

Between October 31 and November 2: Writes “Note on Painting” while on tour in the Southwest with Merce Cunningham Dance Company. The text, which will be published in the anthology Pop Art Redefined (1969), is punctuated with single-word descriptions of sights he sees along the road.

November 22: President Kennedy is assassinated in Dallas.

[Late fall]: Begins to incorporate portraits of Kennedy into approximately eight silkscreen paintings, including Retroactive I and Retroactive II (both 1963). Rauschenberg, who had made the screens prior to the assassination, considers not using the images of Kennedy, then realizes that it would be just as self-conscious a decision to not use as to use them.4 Selects an active, authoritative image of Kennedy and integrates it into a variety of contexts. At the same time, Andy Warhol depicts Jacqueline Kennedy in a series of silkscreen paintings, but his approach is to isolate the image and present it in repetition.

December 6, 7: Rauschenberg provides lighting for Motorcyle, Judith Dunn’s two-day performance program with the Judson Dance Theater, Judson Memorial Church, New York.

- 1. Pierre Schneider, “Art News from Paris,” Artnews (New York) 62, no. 2 (April 1963), p. 48.

- 2. Rauschenberg, “Random Order,” Location (New York) 1, no. 1 (Spring 1963), p. 28.

- 3. Quoted in Robert Rauschenberg, exh. cat. (Washington, D.C.: National Collection of Fine Arts, Smithsonian Institution, 1977), p. 40.

- 4. Forge, Rauschenberg, p. 18.

Rauschenberg: Première Exposition (Oeuvres 1954–1961), Galerie Ileana Sonnabend, Paris, February 1963. Works shown include Monogram (1955–59), Broadcast (1959), and Charlene (1954). Photo: Shunk-Kender © J. Paul Getty Trust

Rauschenberg: Première Exposition (Oeuvres 1954–1961), Galerie Ileana Sonnabend, Paris, February 1963. Works shown include Monogram (1955–59), Broadcast (1959), and Charlene (1954). Photo: Shunk-Kender © J. Paul Getty Trust

Rauschenberg performing his piece Pelican (1963), First New York Theater Rally, former CBS studio, Broadway and Eighty-first Street, New York, May 1965. Photo: Peter Moore © Barbara Moore/Licensed by VAGA, NY

Rauschenberg performing his piece Pelican (1963), First New York Theater Rally, former CBS studio, Broadway and Eighty-first Street, New York, May 1965. Photo: Peter Moore © Barbara Moore/Licensed by VAGA, NY