Susan Weil

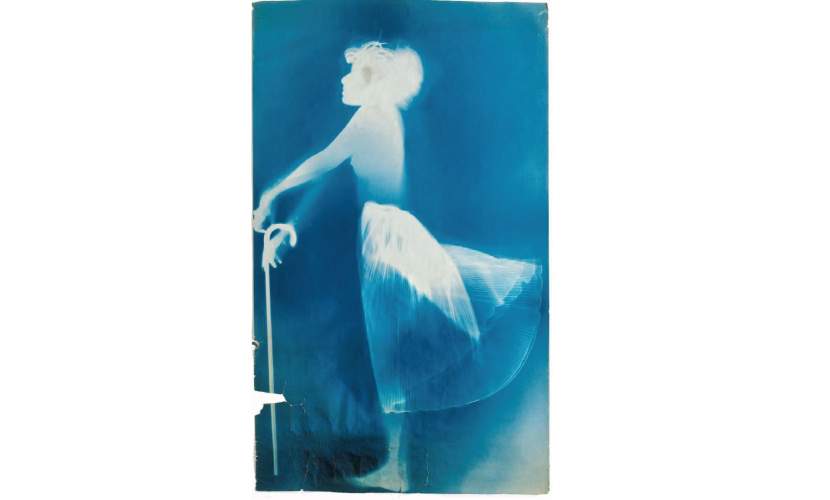

Susan Weil is a painter, a printmaker, and a book artist, who lives in New York. She met Rauschenberg in 1948 when they were both art students at the Académie Julian in Paris. Later that same year, they enrolled at Black Mountain College, near Asheville, North Carolina, and subsequently, at the Art Students League, New York. Married from 1950 to 1952, Weil and Rauschenberg worked closely during those years and collaborated on various projects, most notably the blueprints series (1949–51), which was a monoprint technique that Weil had experimented with since childhood. Their son, Christopher, was born in 1951.

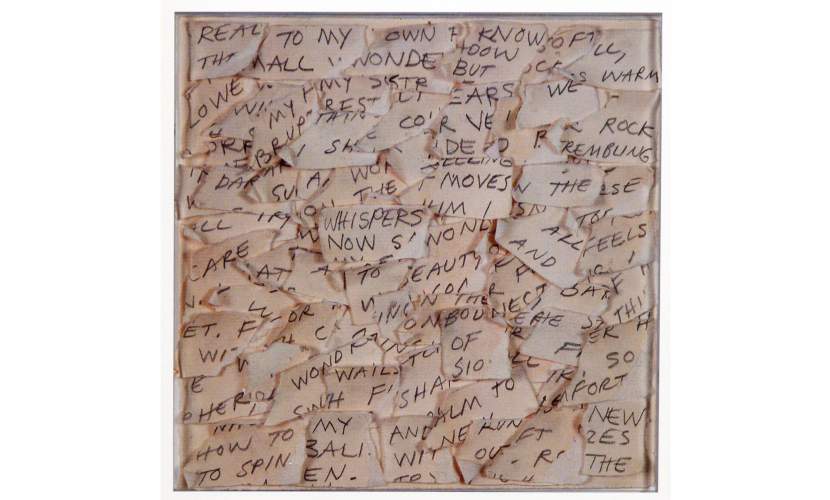

Weil’s work can be found in prominent art collections in the United States and Europe, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; the Museum of Modern Art, New York; and the Moderna Museet, Stockholm. Recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship and a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship, Weil is the subject of several monographic publications and exhibitions, most recently Poemumbles: 30 Years of Susan Weil’s Poem/Images at Black Mountain College and Arts Center, Asheville, North Carolina (2015), and Susan Weil: Moving Pictures (Skira, 2010).

Excerpts from interview with Susan Weil by Mary Marshall Clark, 2014

Weil: Well, [Black Mountain] was very interesting, because it was a very small school, there were almost as many faculty as students. And it was a work-study thing, you had to take care of the school, as well as your classes. But it was so lively, and the very loveliest part of it was, when you had finished your classes, and you went to the dining hall in the evening to have dinner, then you’d sit around and talk with all the other creative people about their day, and you learned so much of the poets, the Black Mountain poets were fantastic. You know, all the different areas, the music people, and so on. And we’d share our experiences. Actually, a lot of times, people would take other classes. I did study a bit in poetry. It was interesting to learn to put together the different creative areas. Of course, this happened at the Bauhaus too. The main reason I went to Black Mountain was because [Joseph] Albers was teaching there and he had been a teacher at the Bauhaus. So, a lot of those traditions also took place at Black Mountain.

Clark: I’m glad you mentioned that, because I was wondering about that, and what some of those traditions were.

Weil: Well, mixing theater and dance, and art, painting—all the different areas. It was very lively. They used to say that the first Happening happened at Black Mountain, but of course there were theatrical happenings all over history, you know. Not only at the Bauhaus, but in Europe in general. The Commedia dell’arte, and so on. So it didn’t really begin in Black Mountain, but it sort of made people aware.

Clark: Before we get to Albers and his stories, can you remember who some of the people were that you had those conversations with in the evening that influenced you? Who was there when you were there?

Weil: Well, at the time, I was taking dance classes. Hazel Larsen and I were in the dance classes, and both of us were disabled people. Hazel couldn’t walk, or anything. But, you know, we were taking the dance classes. Also, I was in the chorus, and I have a terrible voice! And I was singing the B minor Mass and theSt. Matthew Passion, and everything, and I was just having a great old time, you know, studying poetry and everything. I mean, it was wonderful, because you could keep track of what everybody was doing.

Clark: Were Merce Cunningham and John Cage there when you were there?

Weil: They visited there. They weren’t teaching there when I was there. But they visited there, and I did know them, and meet them, and so on. They were dear friends for all of their lives. We did know each other, always.

Clark: So, now let’s turn to Albers, and I’d like to hear, first of all, your impressions of him, and how he taught.

Weil: It was like a modern academy, because he had a way about having us understand about color, and form, and so on. It was pretty rigid. He would say, “You are not an artist, you are a student.” Modesty was very important to him, so therefore, he had run-ins with Bob all the time, because he recognized that Bob had an ego, which was a great thing! [Laughs]

[ . . . ]

Clark: What were some of your jobs at Black Mountain, and how did that come into your work?

Weil: Well, I worked on the farm, and I made butter for the school. And our favorite job was, we were trash collectors. We had the truck, we’d go around all over the school and pick up people’s trash. And Madam Galdowski, my French teacher, she would always make us little presents in her garbage. People got so jealous, because we had such a good time! We’d go to the dump, and it was like playtime! I mean, Bob was that way in the rest of his life, you know, having so much happiness in the dump!